Alternate Title: What Can 24’s Jack Bauer Teach a Tech Startup Founder About Strategy?

Running a business without a strategy is like breathing air without oxygen.

The purpose of this blog post is to attempt to synthesize certain fundamental lessons on strategy that are relevant for anyone trying to build a business. ((Let me know if you feel I have failed to attribute something appropriately. Tell me how to fix the error, and I will do so. I regret any mistakes in quoting from my sources.)) As part of the discussion, I will attempt to provide concrete yet easy to use frameworks that founders of early stage startups can use as they work on moving their organizations through the discovery process that takes them from being a startup to becoming a company. ((My target audience is made up of first-time startup founders who do not have any background in business, finance, economics, or strategy.))

To ensure we are on the same page, and thinking about the issues from the same starting point . . . first, some definitions.

Definition #1: What is a Startup? A startup is a temporary organization built to search for the solution to a problem, and in the process to find a repeatable, scalable and profitable business model that is designed for incredibly fast growth. The defining characteristic of a startup is that of experimentation – in order to have a chance of survival every startup has to be good at performing the experiments that are necessary for the discovery of a successful business model. ((I am paraphrasing Steve Blank and Bob Dorf, and the definition they provide in their book The Startup Owner’s Manual: The Step-by-Step Guide for Building a Great Company. I have modified their definition with an element from a discussion in which Paul Graham, founder of Y Combinator discusses the startups that Y Combinator supports.)) As an investor, I hope that each early stage startup in which I have made an investment matures into a company.

Strategy is about making choices, trade-offs; it’s about deliberately choosing to be different.

– Michael Porter ((Keith H. Hammond, Michael Porter’s Big Ideas. Accessed on Jun 20, 2015 at http://www.fastcompany.com/42485/michael-porters-big-ideas))

Definition #2: What is Strategy? An early stage startup’s strategy is that deliberate set of integrated choices it makes in order to create a sustainable competitive advantage within its market relative to rival startups and market incumbents. It is the means by which a startup combines all the elements within its environment to create and deliver value for its customers, while simultaneously capturing some of that value for itself and its investors. Strategy answers questions about what the startup should do and what it should not do in order to find a repeatable, scalable and profitable business model.

Some additional observations about strategy;

- Strategy can be granular and tangible or broad and intangible. It is granular and tangible as one goes further down the organizational hierarchy. It is broad and intangible as one approaches the top of an organization.

- Strategy helps a startup decide how to utilise its internal and external resources and capabilities towards reaching its ultimate goals and objectives.

- In a growth stage startup or mature company, effective strategy makes choices and trade-offs in the following areas;

- Supply chain

- Manufacturing, product development

- Distribution channels

- Human resources

- Finance

- Research and development

- Operations

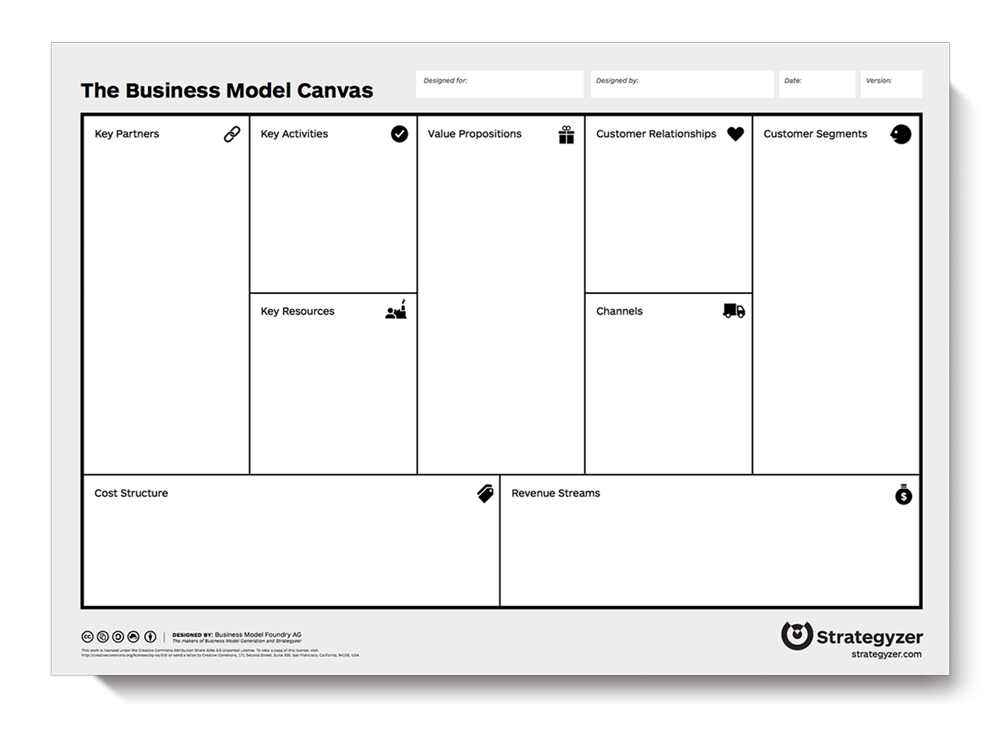

- For an early stage startup strategy involves choices and trade-offs in the following areas;

- Value propositions

- Customers – segments, relationships

- Key activities

- Key resources

- Key partners

- Cost structure

- Revenue streams

Strategic Decision Making Tools for Early Stage Technology Startups

Porter’s 5 Forces: In a 2008 update to his 1979 HBR Article: How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy, Michael E. Porter discusses the “5 Forces” that have a direct impact on strategy.

Threat of New Entrants: This is the degree to which a startup can expect to face intense competition because the number of direct rivals it faces keeps increasing. Direct rivals are other startups that enter the market with a value proposition that is nearly identical to that which a given an incumbent startup is offering its customers. High threat of new entrants imposes a ceiling on profitability, limits how much value an incumbent startup can capture for itself, and imposes high costs on the existing competitors within the industry or market. As a result, it is important for startup founders to think about how they might construct an economic moat around their business. Michael Porter discusses seven major sources of barriers to entry; supply-side economies of scale, demand-side benefits of scale, customer switching costs, capital requirements, incumbency advantages independent of size, unequal access to distribution channels, and restrictive government policy.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Suppliers become powerful when they form a more concentrated group than the startups that they sell to and do not rely on startups for the significant proportion of their revenues. Additional factors leading to supplier power include; the suppliers offer products that are differentiated and unique, startups face high switching costs in moving from that supplier group to an alternative product, a lack of satisfactory alternatives to the product or service provided by the supplier group. These factors combine to put the suppliers in an enormously strong negotiating position, and enables them to maintain high prices and pass nearly all cost increases on to their startup customers.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: This is the opposite of supplier power. Powerful buyers can have a debilitating impact on the profitability of a group of startups that supply them with goods or services. The factors that contribute to powerful buyers are; a small number of buyers with each purchasing in large volumes relative to the size of each incumbent startup, buyers perceive and experience no switching costs if they switch from one startup’s products to products supplied by one of its competitors, the quality and reliability or lack thereof of products or services provided by suppliers does not affect the buyers’ ability to maintain or improve the quality of their goods or services.

Threat of Substitutes: This has not happened recently, but it used to be that when I would ask a founder “Who is your competition?” the quick response would be “We do not have any competition!” I’d shake my head and think to myself, they must not understand the meaning of substitute. According to Michael Porter “A substitute performs the same or a similar function as an industry’s product by a different means.” For example, videoconferencing is a substitute for travel. The threat posed by substitutes can be camouflaged by the apparent difference between the way an early stage startup perceives its customer value proposition and the way its customers perceive that same value proposition in comparison to the substitute. One way to think of substitutes is to ask “How are customers fulfilling that need or solving that problem now?” Another way to think about substitutes is to ask the question “Where are customers spending less money because they have chosen to buy our product?” Industry profitability is constrained by a high threat of substitutes. Consider the threat posed to social-networking like Twitter and Facebook from the chat and messaging apps. Facebook has been more responsive to those threats, and has strengthened its strategic position through its acquisitions of Instagram, Oculus Rift and Whatsapp. The threat posed by substitutes is high if customers are indifferent to the price-performance trade-offs they have to make if they switch to the substitute. The threat is also high if switching costs to customers are minimal, or non-existent. To find examples of how the threat of substitutes functions, think of the threat that Facebook is posing to Google’s business model of selling ads tied to users’ search activity. Or the threat that the shift from desktop-centric to mobile-centric computing poses to all kinds of businesses that have been built from the desktop centric point of view. Or the current debates around the relationship between startups in the on-demand economy and their employees, and the implications for the startups that are currently on either either side of that debate. ((Annie Lowery, How One Woman Could Destroy Uber’s Business Model – and Take the Entire “on-Demand” Economy Down With It. Accessed on Jun 21, at http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2015/04/meet-the-lawyer-fighting-ubers-business-model.html.))

Rivalry Among Existing Competitors: Think Uber and Lyft, Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and Netscape Navigator, Apple iTunes and Spotify/Pandora etc, Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android, Apple’s iPhone and Samsung’s Galaxy, Apple’s Watch and the burgeoning number of wearables designed and produced by other competitors in that market. Evidence of intense rivalries among existing competitors is found in frequent price-cuts, ubiquitous sales and marketing campaigns, and relatively short product and service upgrade cycles. Combined with the threat of new entrants, rivalry among existing competitors leads to a land-grab by incumbents to access new markets where rivalry is less intense and potentially lock rivals in other markets out of the new markets. A land-grab could also be initiated in anticipation of intense rivalry developing in the future. The on-demand ride-sharing wars that are playing out around the world today provide a text-book example of this phenomenon. High rivalry among existing competitors constrains profitability along two dimensions; the intensity of the competition, as well as the basis on which that competition is taking place. Factors that contribute to a high intensity of rivalry are: Competitors roughly equal in size, slow growth, high exit barriers, high levels of commitment to the market and the industry, and poor signaling. One mistake rivals often make? They engage in mutually destructive price-cuts in succeeding rounds of attack and retaliation. Or, they might engage in other tactics that lead to an overall degradation of the customer experience or user experience for their mutual customers. Particularly destructive behavior is most liable to occur when the individual rivals’ products cannot be differentiated from one another by their target customers, the rivals are each faced with a cost structure characterized by high fixed costs and low marginal costs, it is difficult to make quick capacity adjustments in response to surges or declines in demand, and the product is perishable. ((Consider how the transient, perishable nature of “time” has influenced the behavior of ride-sharing rivals – a ride not delivered today can never be recouped. It is gone forever.)) Ideally, competition among rivals should aim to grow the profitability of the industry or market for all players within it, while raising barriers to entry.

Factors that influence strategy: In debates about strategy with other management theorists, academics and practitioners, Michael Porter has stated;

It is especially important to avoid the common pitfall of mistaking certain visible attributes of an industry for its underlying structure.

He describes the following factors that influence strategy and competition within an industry;

- Industry growth rate

- Technology and innovation

- Government

- Complementary products and services

The key is for startup founders and their investors to analyze each of the five forces that shape competitive strategy within the context of each of these factors. The factors are not inherently good or bad, but must be assessed in the context of the the five forces and the impact they have on developments within the industry.

You probably think I’m at a disadvantage; I promise you I am not.

– Jack Bauer (24: Live Another Day); speaking to a group of armed men suspected of planning to carry out a terrorist attack on London. He appears ambushed, trapped, outnumbered and outgunned by them.

Definition #3: What is Game Theory? According to Wolfram Mathworld; “Game theory is a branch of mathematics that deals with the analysis of games (i.e., situations involving parties with conflicting interests). In addition to the mathematical elegance and complete “solution” which is possible for simple games, the principles of game theory also find applications to complicated games such as cards, checkers, and chess, as well as real-world problems as diverse as economics, property division, politics, and warfare.

Game theory has two distinct branches: combinatorial game theory and classical game theory.

Combinatorial game theory covers two-player games of perfect knowledge such as go, chess, or checkers. Notably, combinatorial games have no chance element, and players take turns.

In classical game theory, players move, bet, or strategize simultaneously. Both hidden information and chance elements are frequent features in this branch of game theory, which is also a branch of economics.” ((Game Theory. Accessed on Jun 21, 2015 at http://mathworld.wolfram.com/GameTheory.html))

For a flavor of the wide application of game theory;

- Malcolm Gladwell attempted to apply it to analysis of athletic prowess in this May 2006 article in The new Yorker.

- Michael A. Lewis, then a professor at the Silberman School of Social Work at Hunter College in NYC applied probability and game theory to an analysis of The Hunger Games in this April 2012 article in Wired.

- Clive Thompson writes about a claim by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, a professor at my alma mater New York University and “one of the world’s most prominent applied game theorists” that he could predict when Iran will get the nuclear bomb in this August 2009 article in the New York Times Magazine article.

Playing The Right Game – Using Game Theory To Shape Strategy: In their 1995 Harvard Business Review article – The Right Game: Use Game Theory to Shape Strategy Adam M. Brandenburger and Barry Nalebuff offer advice that startup founders can use to guide the choices they make as they navigate the terrain that lies between their startup’s emergence as an embryonic organization and its hopeful maturity into a company.

Unlike war and sports, business is not about winning and losing. Nor is it about how well you play the game. Companies can succeed spectacularly without requiring others to fail. And they can fail miserably no matter how well they play if they make the mistake of playing the wrong game. The essence of business success lies in making sure you’re playing the right game.

Following are some observations based on their paper:

- There are two basic types of games; rule-based games and freewheeling games. Business is a complex mix of both.

- To aid them formulate their startup’s strategy, the startup’s founders and investors must think far out into the future to make postulations about how the game might unfold by analyzing how all the players in the game will react to moves by another player in the game. This involves reasoning forward and then reasoning backwards to the present in order to determine what actions taken today will lead to the outcome that the startup wishes to bring into existence in the future. They state: “For rule-based games, game theory offers the principle, To every action, there is a reaction. But, unlike Newton’s third law of motion, the reaction is not programmed to be equal and opposite.”

- The startup’s founders must eschew egocentrism and instead embrace allocentrism, i.e. they must focus less on their startup’s actions but rather must focus on the actions, desires, expectations, ambitions, goals, objectives etc. etc. of their rivals. They state: “To look forward and reason backward, you have to put yourself in the shoes—even in the heads—of other players. To assess your added value, you have to ask not what other players can bring to you but what you can bring to other players.”

- Startup founders should seek and create opportunities for “Coopetition” – “It means looking for win-win as well as win-lose opportunities. Keeping both possibilities in mind is important because win-lose strategies often backfire.” They cite the example of a price war as a move that ultimately leaves all the players in a game worse off because it reestablishes the status quo, but at a lower price. Starting a price war is a lose-lose move.

- It is important to think of the players within a startup’s Value Net; an environment created by the startup’s customers and suppliers – arranged vertically in the Value Net framework, and its substitutors and complementors – arranged horizontally in the Value Net. The startup itself is positioned where the Value Net axes intersect. The startup transacts with its counterparties positioned along the vertical axis – resources and money flow between the startup and its customers and suppliers. The startup does not transact directly with its substitutors or complementors, but it interacts with them nonetheless. Often, strategists do not pay sufficient attention to how a startup’s interactions with its substitutors and complementors can be modified in order to create win-win outcomes for the players in the startup’s Value Net. They recommend drawing the Value Net, and monitoring changes that occur to the elements of the game using that map.

- The elements of a game are; The Players – customers, suppliers, substitutors, complementors and, of course, the startup itself. The Added Values – this is what each player brings to the game, and the key task here is to consider means by which the startup might make itself a more valuable player. The Rules – in business these are fluid and likely not transparent, although this is not always so, also the players in the game might agree to change them. Tactics – these are short term moves the startup makes in order to shape how it is perceived by other players in the game, or to maintain uncertainty within the game for its benefit. The scope – these are the boundaries of the game. Founders might consider expanding or shrinking the boundaries of the game in keeping with what they believe works best for the ultimate outcomes that the startups wishes to realize.

- The authors discuss “The Traps of Strategy” – briefly outlined;

- The startup does not have to accept the game that it finds itself in.

- The startup does not have to change the game at the expense of other players within its Value Net.

- The startup does not have to be unique to succeed. On its own, uniqueness is an insufficient dimension along which to pursue success.

- Founders’ failure to study and see the whole game can prove expensive and fatal because any moves towards one group of players in the game has counterpart move with the other players along that axis. Draw the Value Net.

- Founders’ failure to think methodically about changing the game can prove expensive, focusing inwardly on the startup instead of outwardly on the other players within the Value Net limits the strategic options available. Use PARTS.

The Goals Grid – A Tool for Clarifying Goals and Objectives: I discovered The Goals Grid in 2009 while working on two turnaround assignments, and feeling dissatisfied with the tools I had acquired in business school – it quickly became clear to me that those tools did not translate readily when I was in the trenches, working with people on the frontlines of fine-dining, and general aviation, who lacked the training in strategy and management that students in MBA programs in the United States receive. I needed something I could discuss with them, but that they could then implement without me. ((Fred Nickols updated it in 2010. Accessed on Jun 22, 2015 at http://www.nsac.org/Endowments/Docs/GoalsGrid.pdf))

The Goals Grid focuses startup founders’ attention by asking 4 questions;

- What are you trying to achieve?

- What are you trying to preserve?

- What are you trying to avoid?

- What are you trying to eliminate?

It then connects these questions to the problems the startup’s founders seek to solve by rephrasing those questions;

- What do you want that you don’t have? You should be trying to achieve this.

- What do you already have that you already have? You should preserve this.

- What do you lack that you don’t want? Avoid this.

- What do you have now that you do not want? Eliminate this as quickly as possible.

The analyses can be performed using the grid below.

Some observations about the goals grid;

- It is super flexible, and can be used at multiple levels in an organization. It can be used for corporate-wide strategic planning activities as well as team or individual-contributor level tactical planning.

- The ease with which this analyses can be performed make it possible to unshackle the goals grid from our general notions of strategic planning cycles. There is nothing to prevent individuals or small teams within a startup from creating whatever cycle they need to create in order to use the goals grid to accomplish objectives, keep one another accountable. For example in certain circumstances it might make sense to have a monthly goals grid planning and update cycle. In another context perhaps quarterly cycles make more sense. Yet still, in some other context, perhaps weekly goals grid planning cycles make sense.

- While they do not explicitly mention using the goals grid at Pandora, this case study published in the First Round Review shows how powerful a system analogous to this can become – The Product Prioritization System That Nabbed Pandora 70 Million Monthly Users with Just 40 Engineers.

- If it is used, the goals grid should be applied to each component of a startup’s business model while it is in the search and discovery phase of its existence.

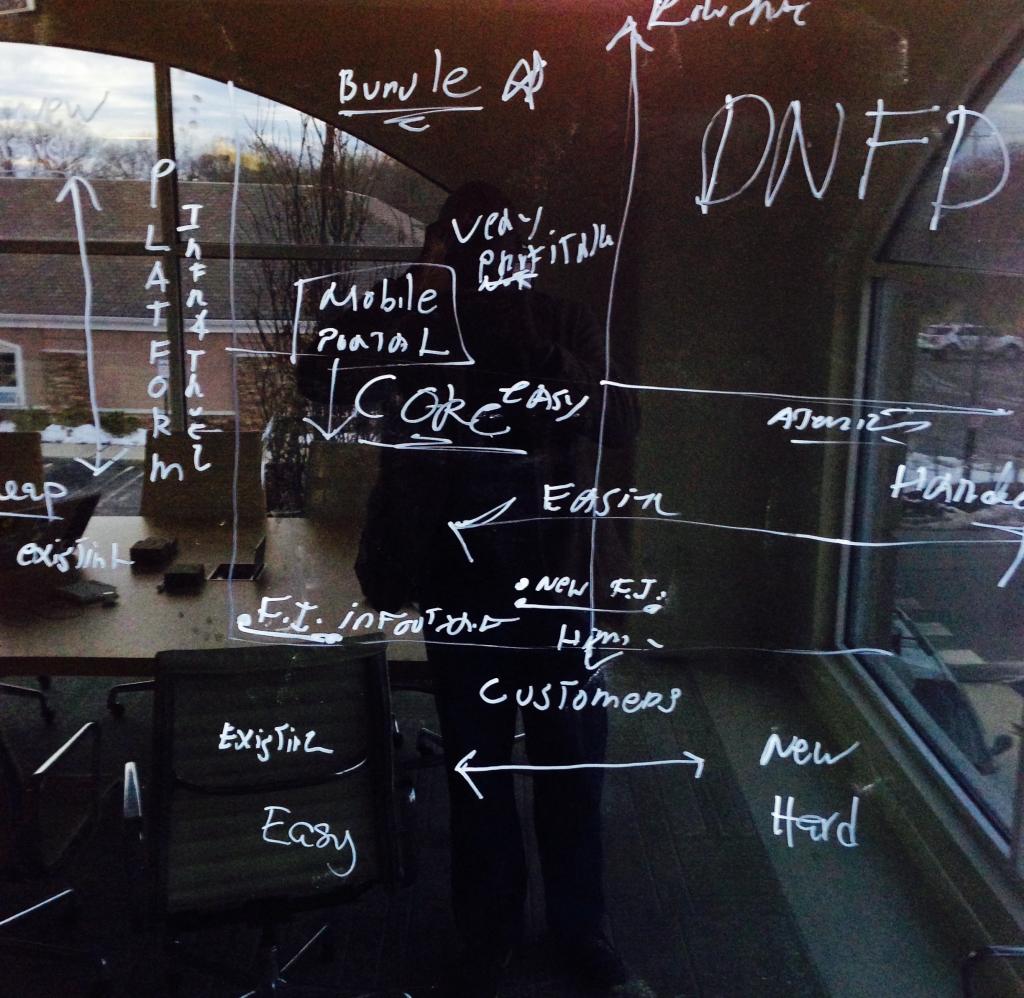

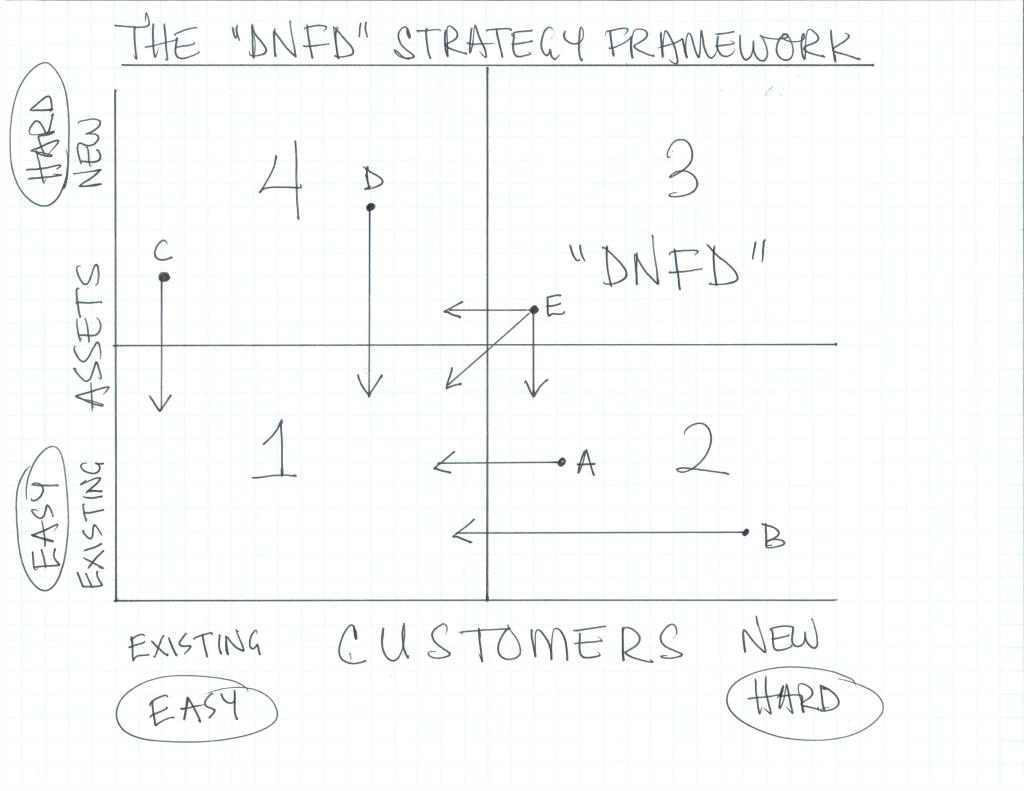

The “Do Not Fucking Do” Framework aka Asset/Customer Reuse Matrix:

Sometimes people who are unaccustomed to thinking about strategy can become paralysed by the volumes of information they have to consider during the process of developing a strategy for an organization; a startup, a company, a corporation, or a division of a corporation. Any kind of organization can use a form of this framework to narrow down its choices.

The vertical axis represents assets or ” degree of asset reusability” while the vertical axis represents customers or “degree of customer reusability”. In the diagram below I have used assets and customers respectively. One difference is that if I had labeled the axes “degree of asset reusability” and “degree of customer reusability” respectively then I would have also had to label them so that they go from “High” near the origin to “Low” as one moved farther from the origin along each axis.

Generally, activities in Quadrant 1 rely on assets that the startup already owns to create new products that the founders believe will be readily accepted and adopted by the startup’s customers. Activities in this quadrant are comparatively “easy” for the startup to execute. Activities in Quadrant 2 and Quadrant 4 are “easy” along only one axis of the decision matrix, they are “hard” or difficult along the other. In Quadrant 2 the startup has to find new customers, which is harder than selling to existing customers. However, it is relying on assets that it already owns, or can very easily obtain. In Quadrant 4 the startup is selling to its existing customers but it is using assets that it does not own, and cannot easily obtain.

Quadrant 3 is the “Do Not Fucking” do that shit region; in this region the startup is developing a product using assets that it does not own, nor can easily obtain, to sell to customers that it does not already have, nor can easily obtain. In this region the startup’s activities are hard along both dimensions of the decision matrix.

As the diagram illustrates the activities labelled A, B, C, and D should relatively easily be migrated from their respective originating quadrants once they are sufficiently mature. In the case of A & B, the new customers stick around long enough for the startup to develop a close and relatively durable bond with them. We can go through a similar thought process for C & D. The key is for startup founders to figure out how to quickly move A, B, C and D into Quadrant 1 as quickly as possible.

The activities labelled E pose a tougher challenge. Generally it is best to avoid them at all cost. Pursuing those activities places the startup at risk of material and substantial loss. Any decision to pursue them requires careful analysis of what it will take to conduct the R&D required to develop the product, as well as estimates of the costs that have to be incurred in order to create demand and win new customers for that product and for the startup. Sometimes its just a matter of timing, but at other times the issues at play are more complex, creating an opaque environment that makes it difficult to make such assessments, and often making it difficult to move those activities into one of the other three available quadrants. DNFD does not mean “don’t do that under any circumstance” but rather “you better have a really good reason for doing that” and so there are situations under which careful strategic analysis leads to one conclusion and one conclusion only . . . You better fucking do that or you’ll get killed. We’ll look at an example below.

Briefly: The DNFD Strategic Framework in Action

- Should Apple produce a tablet? Assume you were assessing Apple’s strategic options soon after it became clear that the iPod/iPhone and iTunes/App Store were going to be wildly successful. How would you decide if it made sense to do more work determining if Apple should develop and market the iPad? Very quickly; first, people who buy iPods or iPhones are likely to want a tablet like the iPad for those activities they no longer enjoy engaging in on their laptop or desktop computers, and for which the customer experience on the iPod or the iPhone is unsatisfactory at best. Moreover, the organizational capabilities that Apple has acquired over the course of time as it has developed the iPod and iTunes, and then the iPhone and the App Store and brought those products to market are easily transferable to developing, producing, and marketing the iPad. ((Obviously more rigorous analysis would have been performed at Apple, but one can see how it makes sense to study this course of action very closely.))

- Should Facebook create its own games? When Zynga announced that it was going to develop its own platform so that it did not depend solely on Facebook as a distribution channel for its games, some people might have immediately assumed that Facebook would rapidly start developing its own games to compete with its one-time partner turned rival, Zynga. The DNFD Framework would suggest that this is not so obvious, from the perspective of an outsider trying to assess the situation. However, one might have asked the following questions; Can Facebook easily reuse its accumulated organizational capabilities to publish games that go on to become immensely popular amongst Facebook’s users? If yes, would these games have a high degree of acceptance and adoption by Facebook’s users? Next, what trade-offs would Facebook have to make in order to start developing its own games? As you can see, these questions are not so straightforward? For example, even though Zynga’s games became immensely popular, one would have to ask how much, on average, of all user activity in a given year on Facebook was devoted by its users to Zynga’s games? Was it significant, noteworthy, or miniscule? As of this writing Facebook has not made any moves to become a publisher of games like Zynga. However, it bought Oculus Rift, a virtual reality device company – it is not yet clear what that means for the prospects of Facebook/Oculus entering the game publishing business. I would not hold my breath if I were you.

- Should Facebook build its own data centers? It is late 2008 and youhave been asked to conduct an analysis on the subject: Facebook should build its own data centers; Yes or No? Your analysis will form the basis of the direction Facebook takes on this issue. What would your conclusion be?

- What is Facebook?

- What is Facebook’s business?

- Why should Facebook be concerned about building its own data centers? Think 5, 10, 15 years out.

- Who is the customer? What are the assets? Will the customer readily and willingly adopt the product?

- Can Facebook afford to fund the R&D and other costs associated with building its own data centers?

- What are the opportunity costs that Facebook will confront if it does this?

- What advantages will Facebook gain? What disadvantages will it face? Does one outweigh the other?

In What Format Should A Strategic Plan Be Maintained? The goal of strategic planning is to create a map that guides the actions of the people in an organization. Good strategy is inextricably linked to execution, and operations. It is management’s responsibility to ensure that strategy is understood to sufficient depth and detail, by everyone in an organization, within the context of the different roles and responsibilities that different people bear and fulfill.

A strategic plan should cover:

- Product

- What features of the startup’s product are critical for this stage of the startup’s life cycle?

- For example, what features should the minimum viable product include? What should it exclude? Why? ((The minimum viable product is the least expensive product that allows the startup to test the most important hypothesis on which its business model depends.))

- How is the startup going to identify its customers? Why do those customers buy the product? Why do those potential who do not buy the product make that choice? What will cause them to change their mind?

- What features does the product need to have if it is going to help the startup win its market?

- What does the landscape of features look like for competitive or substitute products within the startup’s market and Value Net, how should the product be positioned relative to that landscape? Why? What are the trade-offs resulting from those choices?

- What features of the startup’s product are critical for this stage of the startup’s life cycle?

- Finance

- How will the startup increase revenues?

- How will the startup reduce costs?

- Operations – see related discussion in: Why Tech Startups Can Gain Competitive Advantage from Operations

- How will the startup get better at creating its products?

- How will the startup get better at delivering its products to its customers?

- How will the startup ensure that its operations infrastructure does not become obsolete?

- How will the startup ensure that its operations become a source of sustainable competitive advantage and differentiate it from its competitors, while protecting and enhancing its current chosen position in its Value Net?

- How will the startup ensure that its operations infrastructure do not lock it into a position that becomes competitively disadvantageous?

- Growth

- How will the startup gain new customers?

- How will the startup strengthen its bonds with its existing customers?

- How will the startup win back customers it has lost?

- How will the startup expand into new markets?

- What adjacent markets should the startup consider entering? What risks will it face in doing so?

- What new geographic markets should the startup consider entering? Why? Why no?

- What does the startup need to do in terms of marketing, sales, advertising and public relations as those activities relate to the startup’s growth?

- People

- What does the startup need to do in order to attract and retain the best people it can find to help it accomplish its stated goals and objectives?

- How should the startup develop the people on its existing team?

- How does the startup motivate its people, and empower them to accomplish things they previously did not know or believe they could accomplish?

When I have collaborated with others in creating strategic plans in the past those plans started out as notes in my notebook. Then they migrated to notes in a word processor, and finally to a presentation deck that management could use to guide organization-wide conversation about overall strategy, as well as brief summaries, explanations, examples and ideas to help managers communicate the message down the organization. However, the most important work started at the front-lines; studying customers, talking to be people directly doing the work that leads to the creation, delivery and fulfillment of the organization’s value proposition to its customers. That is where the real work of creating strategy occurs.

A strategic plan should be readily and easily accessible to everyone in the organization, and should be updated as frequently as is necessary to suit the startup’s goals and objectives.

Closing Notes

- This blog post has covered a lot of ground, not all of which is applicable to every startup at this moment. However, even a startup that is made up of two engineers developing the early versions of a software product needs to make choices regarding what they should build. That startup needs a strategy.

- Strategy should not become stagnant once it has been developed, it should evolve and adapt to the changing circumstances that a startup finds itself in.

- In thinking of a how startup develops a competitive advantage I am thinking of of how it combines the resources that it controls which help it search for a repeatable, scalable, and profitable business model. These resources might be tangible or intangible.

- A related issue is how the startup influences its external environment and the factors that influence competition such that those factors do not cause it harm.

- A startup has a competitive advantage when it is implementing a strategy and a business model that cannot simultaneously be implemented by its current or potential competitors. It has a sustainable competitive advantage when its strategy and business model cannot simultaneously be implemented by current or potential competitors, and when those competitors cannot duplicate the benefits of that strategy and business model. ((Jay Barney, Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. 1991, Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. 1. Accessed online on Jun 23, 2015 at http://www3.uma.pt/filipejmsousa/ge/Barney,%201991.pdf))

- The startup’s culture is an important source of competitive advantage, and ought to work in concert with its strategy. For example, employees of Facebook should “Move fast, and break things.” within the tenets of its strategy. When Andy Grove “Let chaos reign.” at Intel he did so within the parameters of Intel’s strategy. ((See for example; Jay B. Barney, Organizational Culture: Can It Be a Source of Sustained Competitive Advantage? The Academy of Management Review, 07/1986))

Further Reading: These notes are intended only as a starting point. Below some books that you should consider reading.

- The Management Myth: Debunking Modern Business Philosophy

– Argues, not unreasonably, that there’s no evidence that competitive advantage can be created in advance, and takes issue with Michael Porter’s ideas about competitive advantage. Personally, I am less interested in arguments between academics, and more interested in understanding how people who need to run a business can get better at day-to-day, and long-term execution. The key is to get better at making sensible trade-offs in the present, in order to increase the odds of success in the future. No one can predict the future. Anyone who makes such a claim is a liar.

- The End of Competitive Advantage: How to Keep Your Strategy Moving as Fast as Your Business

– Argues that Porter’s ideas lead to a dangerous complacency; eventually creating the inertia that ensures that entrenched incumbents get displaced by nimble upstarts. In other words competitive advantage is transient, not permanent.

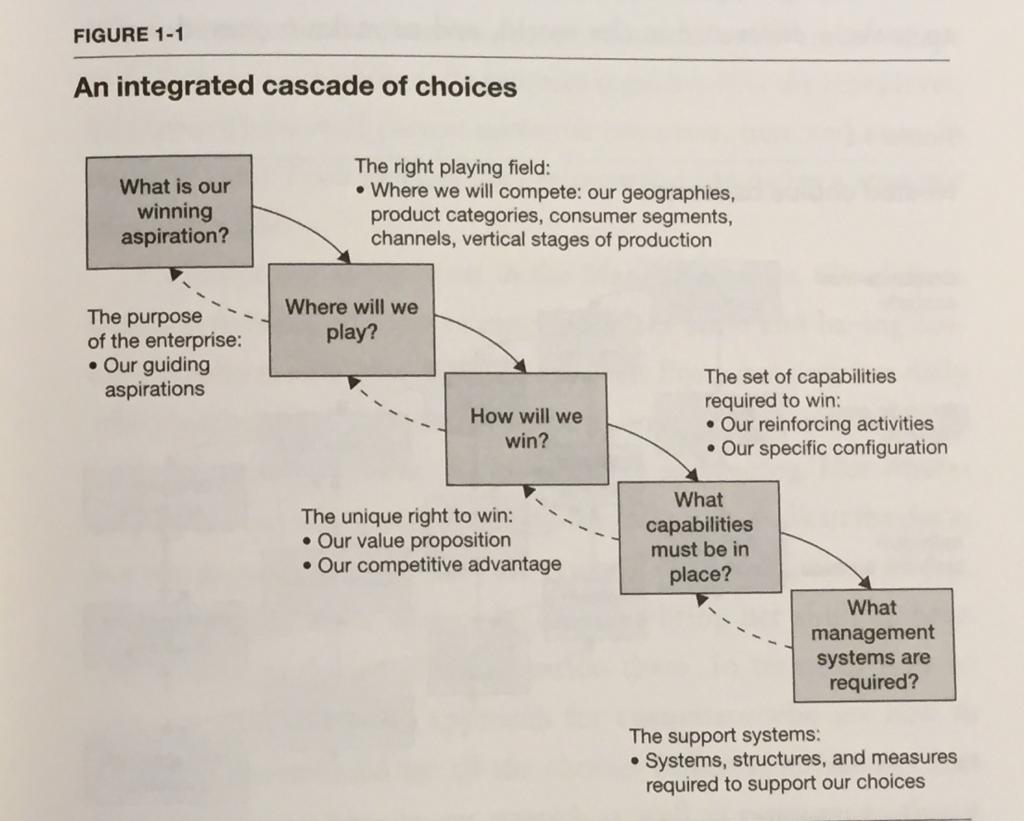

- Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works

– Practical examples of how to make strategic choices for people managing any kind of organization. Arms readers with a definition of strategy, the Strategy Choice Cascade, and the Strategic Structuring process.

- Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters

– Departs from other books on strategy by focusing on a range of fundamental issues that have received little attention. It deals more with the day to day issues strategists must confront, and less with the conceptual arguments about competitive advantage. I wish it existed in 2008/2009 when I needed to translate what I had been taught in business school with real-world scenarios with which I had to contend. Hindsight analysis is easy, developing a forward-looking strategic plan that will work is more difficult. This book focusses on helping illuminate how you can get better at the latter.

- Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…And Others Don’t

& Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies (Harper Business Essentials)

- Small Giants: Companies That Choose to Be Great Instead of Big

[…] el artículo de innovation footprints recogen desde el business model canvas, a las cinco fuerzas de Porter, pasando por el DNFD –Do […]